Germanic Picts In Pre-Norse Scotland?

Evidence for a West-Germanic Language in pre-Alba Pictland.

In Roman Times, the word “Pictish” meant anyone that lived beyond the Roman frontier, especially anywhere north of Roman controlled Britain. By the early middle ages, the word “Pict” transformed from meaning any Briton who wasn’t Romanized to a discrete ethnic identity. The framed Anglo Saxon Bede described the Picts as coming from a region known as Scythia, modern Eastern Europe or the Baltic.

The Welsh born Celtic scholar John Rhy concluded that Pictish was a “pre-Aryan” language, a speculation that might have influenced the fictional “Picts” of the Texian Robert E Howard.

Many have tried to interpret the ogham inscriptions left by these mysterious people through Celtic Language lines, though each translator seems to have his or hers own “translation”. What is lacking in these attempted translations is a European language other than Celtic. Remember, the Picts lived on the Western edges of Scotland, short sea travels away from Scandinavia and Germania. i have study a significant amount of Old Germanic languages, such as Old Saxon, Old High German, and Old Norse.

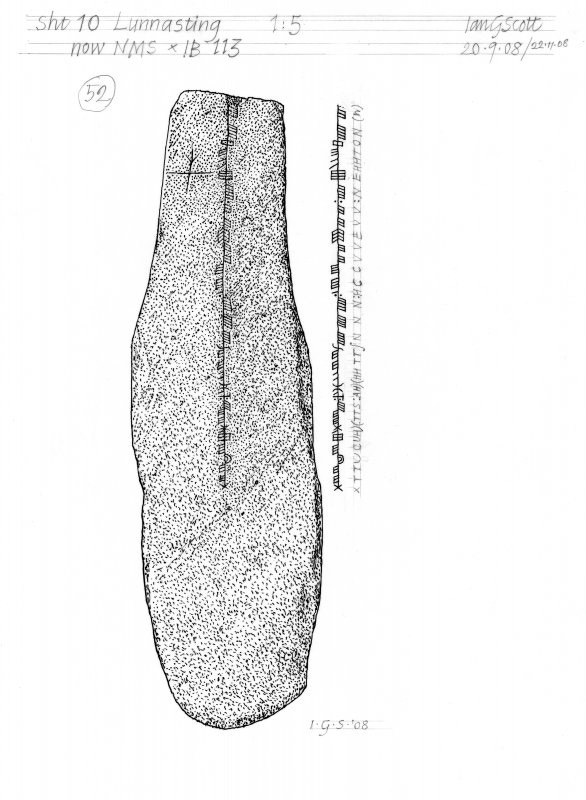

Here is the famous Lunnasting Stone with its infamous inscription ettecuhetts: ahehhttannn: hccvvevv: nehhtons. Located on Lunnastring, on mainland Shetland.

The first thing I notice is the word Ahehhttannn, with reminds me of the Old Saxon word ahebbian: to bring about, to make happen. (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 277). Ettecuhetts could be cogent with Old High German eruuacta/er-wreken/ar-wrecken: to raise upwards, awaken from rest(Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 142). Lazarusan gishahin then her eruuacta from tode.

The possible prefix “ette-” could be related to the Old Norse átti: to process, attain, or have done (Jesses L. Byock, Viking Language 2, page 288).

Hccvvevv, given the possible contest, maybe related to the modern English hack “to cut onto surface”. Old High German hacchon, Old Norse höggva (Etymonline.com, Hack). Nehhtons is obliviously a personal name, likely a spilling of the name Nechtan found in the historical record.

On the Broch of Burrian on Orkney, there’s another ogham inscriptions that is read as I[-]irann uract cheuc chrocs that looks very much similar to the line uuirdit denne furi kitragon frono chruci: “become onto the framed cross, which he carry” (Muspilli, line 100). Irann could mean “within” or “to go one”, Old Saxon and Old High German innan (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 295). Or it could meant to “go on”. With the prefix element “ir-” found in Old High German words like ir-thenken: to think. ir-geban: to give(Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 154). With “-ann” being “on”. Old High German Anna, Old Saxon an(Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 279, 333).

Uract sounds to be a past-tense form of a word related to Old High German uuridit/werdan: to turned into or become (Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 166). And Old Saxon weroan: to come to, to become (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 312).

Cheuc sounds to be the same as the Old Saxon word kuo (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 296) and the Old High German word chud as pronounce in the poem the Hildebrandslied. chud was her..... chonnem mannum. “Known was he, a challenging man”. chud ist mir al irmindeot “all the great ones, I do know”. ( Hildebrandslied, lines 13, 28).

Chrocs is definitely referring to the Christine Cross. “Go on, to become the known Cross” or “know to become onto the cross” is my hypnotized translation. The passage is a reference to Jesus.

Here is the Bressay Stone from Shetland. A recurring theme among the images are the “meeting doubles”. Two humanoid figures with canes appeared on both sides. one of the images, depicts two four legged animals engage in some kind of “kiss”. On onside, there is a male boar or big with a lion like beast on topped. The ogham reads as ᚛ᚉᚏᚏᚑᚄᚄᚉᚉ᚜ : ᚛ᚅᚐᚆᚆᚈᚃᚃᚇᚇᚐᚇᚇᚄ᚜ : ᚛ᚇᚐᚈᚈᚏᚏ᚜ : ᚛ᚐᚅᚅ[--] ᚁᚓᚅᚔᚄᚓᚄ ᚋᚓᚊᚊ ᚇᚇᚏᚑᚐᚅᚅ[--]᚜

CRRO[S]SCC : NAHHTVVDDA[DD]S : DATTRR : [A]NN[--] BEN[I]SES MEQQ DDR[O]ANN[--

Crosscc is clearly meant cross. A lot of attempted translations were state in “memory of Nahhtvvdedd’s daughter An..”. NAHHTVVDDA[DD]S seems to be a spelling of the name Nechtan, found in King lists and the historical record. Dattrr, as notice by many others before me, sounds almost exactly as the Old Norse Dottir (Jesses L. Byock, Viking Language, page 335). Though I don’t think that Ann is a personal named. I hypnotized that its the version of our modern English word and, Old Saxon endi (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 283), Old High German inti(Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 155).

BEN[I]SES MEQQ DDR[O]ANN[-- is the most debated potion of the inscription. BEN[I]SES is a spelling of the Celtic word Brenin: which means king or ruler (John Strachin, An introduction to early Welsh, page 249). Meqq could be a Celtic loan word for “son” or “dissented from” such as the Irish word Mac. It could also be related to the Old Saxon Mag: relative, from the same family (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 299). DDR[O]ANN is a word that appears on the Brandsbutt Stone inscription, and it seems to be a descriptive. I think it meant “of Dunadd” as in the kingdom of Dal Riata. it will make sense for the Gaelic speaking rulers of Dal Riata to adopt a Welsh term for kingship, if they wanted to project power down south. In the same way that Akkadian and Hittite rulers had adopted the Sumerian word for kingship, Lu-gal. I read the inscription as “Cross, Nectan’s Daughter and the Brenin of the Dunaddians (Dal Riata)”. The stone wasn’t a funerary marker but a marriage movement between a Pictish Princess and a king or prince from Dal Riata. Which dates this around the early 7th century Ad, when Dal Riata was reaching its influence to the islands Northeast of Scotland, such as Orkney, Shetland and possibly beyond.

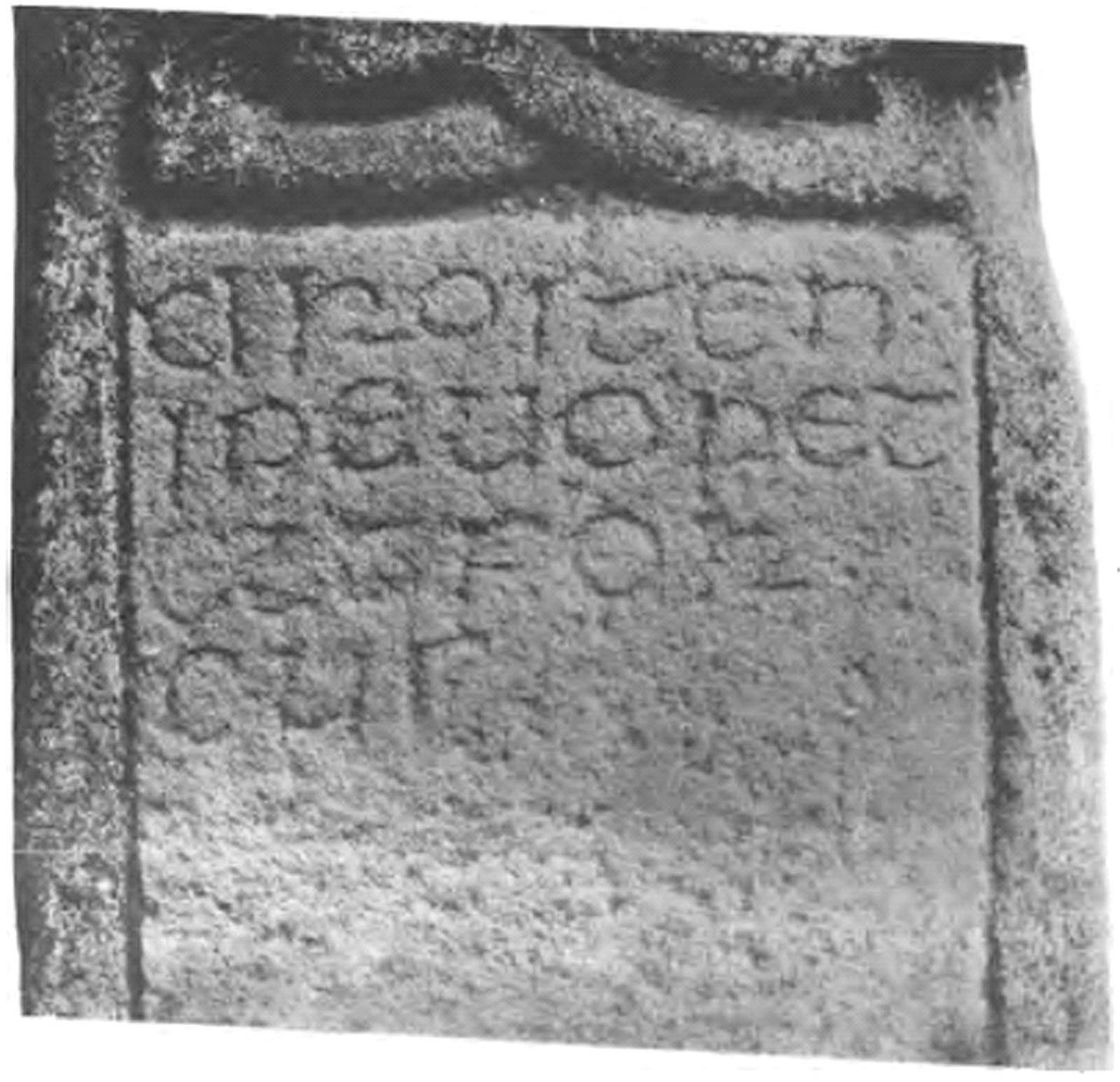

The Drosten Stone is a famous artifact discovered in St Vigeans near the Eastern coaster town of Arbroath. Usually be read as

DROSTEN:

IPEUORET

[E]TTFOR

CUS

Drosten sounds to be related to Old Saxon Drohtin: lord, master (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 282). And Old High German truhtin (Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 164).. It could also be the same as Old High German Trosten/Drosten: to console one about (Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 164).

Ipe- sounds similar to Old Saxon ipu: if, whether, perhaps(Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 342) and Old High German ibu: if, whether or not (Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 154). And there is -uoret, which sounds exactly the same as our modern English word word and Old High German wort (Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 167). Or it could be the same as Old Saxon werod: groups, people, persons (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 312). Ett- could be either related to Old Norse átti (Jesses L. Byock, Viking Language 2, page 288) or Old Saxon eht (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 282). Both words can be used in contests to describe the act of possession or inhabitation. -For can have a similar or exact usage or our modern English word for, which have the exact same usage in Old Saxon (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 286). Cus, I have a intuition of being the same as Old Saxon gest: spirit (Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 287). And Old High German geist: sprit or ghost (Joseph Wright, An Old High German Primer, page 150). My hypothesized translation “Council’s word, if spirit possessed”.

[Edit] Cus could be instead a form of the Old Saxon Kust/cos: to decide on, to choose onto Irmemngard Rauch, The Old Saxon Language, page 297). Example Côs imu [jungarono] thô “of those in service, he choose” (Heliand, fit 37, 3107).

Foreword:

Any interpretation of these inscriptions will only be falsified or proven by new found Pictish texts. Like Minoan and other poorly understood attested languages, the main barrier to our understanding is the lack of longer texts, something like a Pictish version of the Gothic Bible. Hopefully future discoveries may finally end the centuries long debate as to where the Medieval people that we refer to as the “Picts”, belong in the linguistic picture of Europe.

The inscriptions that I suspect to be “Germanic” are found in areas of the Northern most Islands and Eastern most coast. First Millennial AD Pictland, could have been linguistically diverse, with communities of both Celtic and Germanic, and possibly none-Indo-European speakers. Though future evidence could reveal something totally unsuspected.